What should and should not be logged

[Section 1, Part 1] The technology used is only as good as the log events themselves, regardless of how log entries are generated, whether applications write to stdout, stderr, OS event frameworks, or logging frameworks. To maximize the technical investment, we need to make the log events and their creation as effective as possible.

This excerpt will explore what should and should not be logged in terms of business data, and it will examine what information can make log events more helpful.

With that, we’ll identify some practices to help get values from the log events. The business data our systems process can be subject to a wide variety of contractual and legislative requirements. So we’ll look at:

- Some of the better-known legislation needs

- Some options to mitigate their impact

- And sources that can help us identify any other legislative requirements that can impact the use of logging.

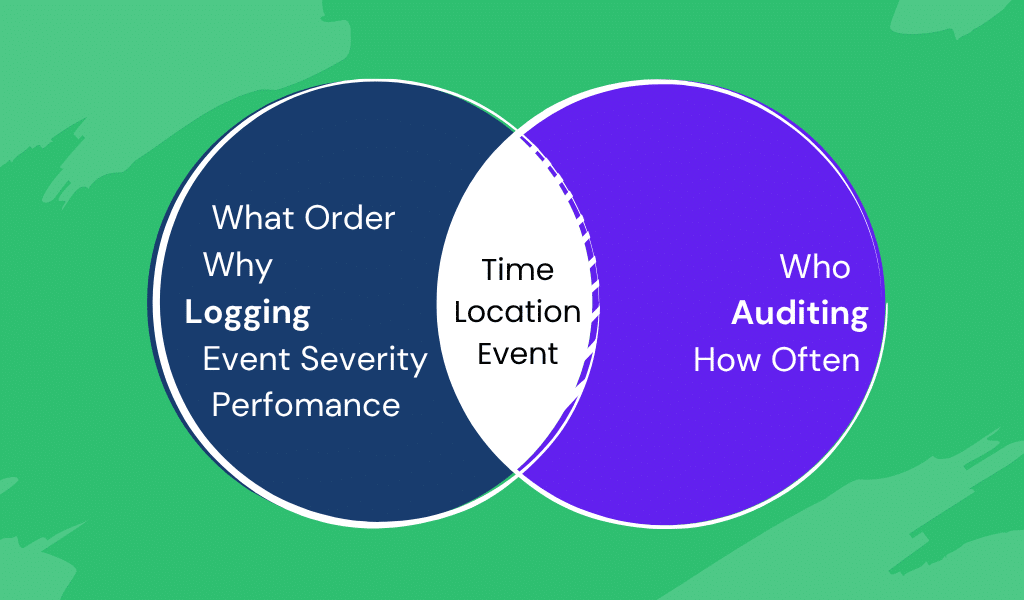

Audit events vs. log events

When is an event an audit event, and when is it a log event? Let’s start with defining what the two events are:

- Audit events—These are typically a record of an action, event, or data state that needs to be retained to provide a formal record that may be required at some future point to help resolve an issue of compliance (such as accounting processes or security). Many of these actions will be user-triggered.

- Log events—These record something that has occurred; the log event will be provided for a technical reason, ranging from showing how a transaction has been handled, to reporting unexpected circumstances, to show how code is executing.

Venn diagram showing the relationship between logging and auditing

Of course, the key to this is a common understanding of what the log level represents. Misclassification of log entries is a common mistake with log events, which is why we’ve mentioned the possibility of correcting those issues using Fluentd. But this also means we should be explicit and that teams agree on the meaning of the levels.

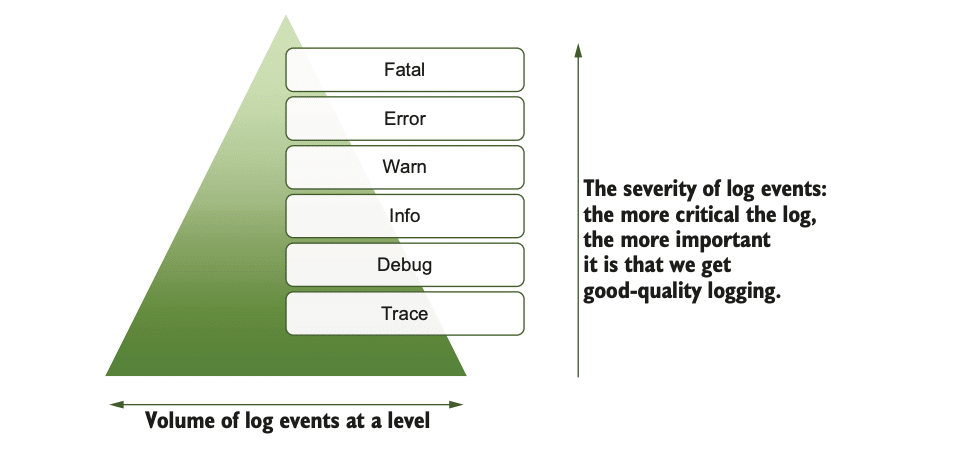

Log levels and severities

Some logs help development and testing, others help with troubleshooting, and still others help with audit, security, and performance tracking. The simplest thing that can be done is to attribute every log with a log level, or severity, reflecting the impact of what the log event represents.

Typical log levels are trace, debug, info(rmation), warn(ing), error, and fatal. The idea of event severity and these severity levels goes back to the ’80s and Syslog development. Many aspects of how Syslog does things have become standards with the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force.) But there is a correlation between these levels on the associated activities, as we’ll see in a moment.

Of course, the key to this is a common understanding of what the log level represents. Misclassification of log entries is a common mistake with log events, which is why we’ve mentioned the possibility of correcting those issues using Fluentd. But this also means we should be explicit and that teams agree on the meaning of the levels.

The following sections provide a common set of log level definitions.

Trace

Primarily for development activities, the execution can have simple events written to the log to indicate what method is executing. This allows us to confirm/validate that execution paths are as expected.

When it comes to the ideas of open tracing and open telemetry, we do need to separate these from the classification. These technologies collect “trace” information showing how a “transaction” has flowed through our environment.

Open tracing depends on the granularity of the tracing implemented. If the trace reflects the technical steps of what is executed during the transactional flow, for example, in and out of components, functions, and so on, then we will see a fine-grained and comprehensive trace, and it should be logged using a trace categorization.

If the tracing reflects the business perspectives (e.g., executing all the actions related to getting goods into a warehouse), then we’re going to see coarse-grained details, and this is best logged at an information level.

Debug

This level is intended for sharing logging data to support any development and debugging activities. This logging level should be information-rich to make troubleshooting easy or to re-create an operational issue, since it will yield the most insight into what the software is doing. The content of such information should be produced with both developers and those involved in more detailed troubleshooting. We often see this level of logging being used rather than trying to use an IDE debugger and attaching it to running software.

These log messages are the most vulnerable to accidentally logging too much information (e.g., personal or financial data), as whole data objects can be easily logged. This shouldn’t be an issue in non-production environments since the data is likely to be synthetic. This also means it is easy to overlook the risks for production.

The risk of logging sensitive data could be addressed by:

- Developing standards that include details to address what data is or isn’t logged and testing processes to ensure synthetic event data isn’t logged.

- Putting a blanket ban on enabling debug-level logging in production (production should never have debug-level logging). In the event of a serious operational issue, the temptation to help diagnose a significant operational issue will be high, and the consequences of setting debug-level logging are overlooked until it’s too late.

Info(rmation)

This is the typical threshold for logs in everyday operational environments. It should provide sufficient log information that diagnostic tasks can be undertaken if a system doesn’t appear to be behaving correctly. The information recorded should include details like:

- Software versions, and so on, logged during startup and deployment.

- Audit logging, such as what and who, through details like session IDs (this brings challenges involving personal data security, which we’ll discuss in more depth later).

- Data values that influence decision logic.

- Interaction with sources and targets, such as URIs for other services, databases.

Manning book: Logging Best Practices

Transform logging from a reactive debugging tool into a proactive competitive advantage.

Warn(ing)

When things are not working as expected, there is a risk of an error, but the software can continue to execute. For example, database connections fail, and the code supports a rollback or a successful retry operation. This may result in a warning to say that it failed to connect, and then an error if it retries, or a complete rollback and the transaction being abandoned.

Warnings should not require immediate intervention but should be indicative of the possibility of remediation being needed. This should include handling unexpected paths, and therefore assuming an action.

Warnings ideally are linked to operational guidance documentation such as advising that maintenance processes may need to be performed sooner than the maintenance schedule would lead us to expect, or that mitigation actions have been automatically taken, such as scaling up a resource. Other warning actions may include reviewing how a transaction has been completed as the system hasn’t processed it conventionally or the code has assumed something incorrectly.

We should also think about our solutions being defensive, checking if things are getting close to dangerous thresholds, and creating warnings. For example, this might include ensuring there is disk capacity to cope with the current rate of data growth. Other defenses should include validating data received, even if it originated from a trusted source.

Error

This is used to record an event that will require intervention; for example, performing an operation on an empty data structure that is assumed to always have a value can trigger a null pointer exception. This will likely create a situation where a process does not complete cleanly and thus needs to reflect as an error.

For logging to help with error resolution, the log events need to clarify the error cause. The location in the code where the error occurred is crucial in order to enable improvements to be effectively applied. This means a developer needs consumable information in an error log event to help implement improvements, and Ops need details to determine what remediation is needed.

When errors occur, not only do we need a fix, but the errors also need to have operational corrections applied to data (e.g., dividing by zero results in a calculated value not being updated). Therefore, the information must also be clearly understood by Ops people and the development/support team. Error codes can be beneficial, as the remediation steps can be documented without swamping code with lots of text.

Errors should try to fail gracefully—that is, they are handled and minimize the disruption (e.g., record the requested transaction and then allow subsequent transactions to be processed without being tainted if possible).

Fatal

This kind of error should only be used in exceptional circumstances, such as when the application has to terminate unexpectedly. The termination is likely to be ungraceful. As with errors, the information needs to be as comprehensive as possible. However, with a fatal error, there may be limitations on the information that can be gathered— for example, a fatal error because of a failed file system will limit the ability to grab related data values that may have influenced the cause of the problem.

Again, error codes can be helpful, both to direct recovery tasks and by providing indications to underlying causes without resorting to having to build nice error messages.

Extending or creating your own log levels

These definitions do not mean you can’t formulate your own levels, but they have significant implications in using a framework and ensuring common understanding. For example, from time to time, I have wondered whether the error level should be split— some errors demand immediate intervention, as they are a precursor to a fatal event if you don’t intervene. And some errors mean a bad outcome, but they can wait until regular operating hours to be resolved.

Consider an overnight payroll run—the calculation of the pay for one individual has failed because the formula didn’t allow for someone being paid for 0 hours one month, triggering an error such as dividing by zero. While this is an error and needs addressing, should it stop the payroll run for everyone?

The log levels have a hierarchy of severity, and with that comes a frequency of occurrence. Trace logs are likely to be pretty pervasive, but fatal log events should be very rare. We can see this in the figure below If we add a new log level, how does it fit into the hierarchy?

While creating additional or different log levels is possible, I have concluded that changing log levels from industry norms is like swimming against the tide and have settled on clearly worded definitions of log levels. If you’re considering customized log levels, the bottom line is to be prepared for a considerable amount of effort, from communicating the log-level details to figuring out everything impacted to determining the log framework settings.

Should audit events use log levels, given the overlap previously described? Typically, audit events should be benign in nature and as a result should be logged at the info level as indicated in the Info(rmation) section a few chapters prior to this.. However, if your auditing includes financial considerations, then failed transactions such as credits/debits to an account balance should form part of the audit trail and reflect the event’s significance. As such, events may require manual intervention, which will create subsequent audit events showing possible interventions. It is worth considering the possibility of linking the log events together to enable better insight.

Standardizing language for both machines and human

The why and how of logging is foundational to making logs useful

Now that we know what to log, the next step in maximizing log value is standardizing language for both machines and humans. Context is essential—especially when using trace and debug logs across development and production. In the next article, we’ll explore how to make logs truly actionable and easy to interpret, even for those with different backgrounds or native languages, for more seamless tracing and diagnosing.

Frequently Asked Questions

What types of log data should organizations collect?

Organizations should collect logs from all relevant sources, including applications, infrastructure, network devices, security systems, and cloud services. This ensures a complete and actionable view of operations.

How can logs be structured effectively for analysis?

Logs should be grouped into categories, use standard log levels (e.g., debug, info, error), employ tags for context, and be formatted in consistent, machine-readable standards like JSON or XML for easy analysis.

Why is consistent formatting important in log messages?

Consistent text formatting, such as standardized date/time formats and naming conventions (camel case or snake case), makes logs easier to interpret, troubleshoot, and automate for downstream analytics.

What contextual data should be included in log entries?

Valuable contextual data includes precise timestamps, user IDs, IP addresses, hostnames, application IDs, and transaction IDs to make logs useful for tracing, auditing, and incident response.

What are the best practices for securing and managing privacy in logs?

Best practices include encrypting logs in transit and at rest, redacting or masking sensitive information, enforcing access controls, and performing regular audits to ensure compliance with regulations.

Explore Chronosphere's Log Feature

Learn how Chronosphere Logs offers seamless integration with metrics and traces, providing a unified platform and an enhanced user experience.