In chapter 2 [of the Manning Book: Platform Engineering on Kubernetes] we created abstractions such as databases and message brokers to provision and configure all the components required by our application’s services. This platform enables teams to request new development environments that not only create isolated environments but also install an instance of the Conference application (and all the components required by the application) so teams can do their work. By going through the process of building a platform, we defined the responsibilities of a platform team and where each tool belongs and why.

So far, we have given developers Kubernetes clusters with an instance of their application running. This chapter looks at mechanisms to provide developers with capabilities closer to their application needs. Most of these capabilities will be concerns accessed by APIs that abstract away the application’s infrastructure needs, allowing the platform team to evolve (update, reconfigure, change) infrastructural components without updating any application code.

At the same time, developers will interact with these platform capabilities without knowing how they are implemented and without bloating their applications with a load of dependencies. This chapter is divided into three sections:

- What are most applications doing 95% of the time?

- Standard APIs and abstractions to separate application code from infrastructure.

- Updating our Conference application with Dapr (Distributed Application Runtime), a CNCF and open-source project created to provide solutions to distributed application challenges.

How do applications work?

We have learned how to run it on top of Kubernetes and how to connect the services to databases, key-value stores, and message brokers. There was a good reason to go over those steps and include those behaviors in the walking skeleton. Most applications, like the Conference application, will need the following functionality:

- Call other services to send or receive information: Application services don’t exist on their own. They need to call and be called by other services. Services can be local or remote, and you can use different protocols, most commonly HTTP and GRPC. We use HTTP calls between services for the conference application walking skeleton.

- Store and read data from persistent storage: This can be a database, a key-value store, a blob store like S3 buckets, or even writing and reading from files. For the conference application, we are using Redis and PostgreSQL.

- Emit and consume events or messages asynchronously: Using asynchronous messaging for communicating systems implementing an event-driven architecture is a common practice in distributed systems. Using tools like Kafka, RabbitMQ, or even cloud-provider messaging systems is common. Each service in the Conference application is emitting or consuming events using Kafka.

- Accessing credentials to connect to services: When connecting to an application’s infrastructure components, whether local or remote, most services will need credentials to authenticate to other systems. In this book I’ve only mentioned tools like external-secrets or HashiCorp’s Vault, but we haven’t dug deeper into it.

Whether we are building business applications or machine learning tools, most applications will benefit from having these capabilities easily available to consume. And while complex applications require much more than that, there is always a way to separate the complex part from the generic parts.

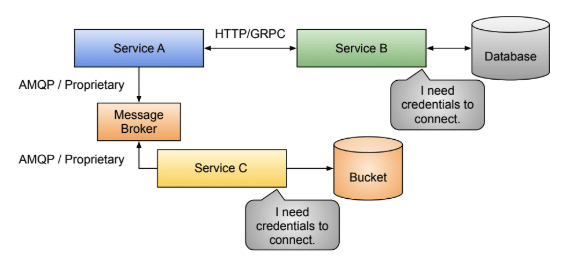

The figure below shows several example service interactions with each other and available infrastructure. Service A is calling Service B using HTTP (for this topic, GRPC would fit similarly). Service B stores and reads data from a database and will need the right credentials to connect. Service A also connects to a message broker and places messages into it. Service C can pick messages from the message broker and, using some credentials, connect to a Bucket to store some calculations based on the messages it receives.

The figure below shows several example service interactions with each other and available infrastructure. Service A is calling Service B using HTTP (for this topic, GRPC would fit similarly). Service B stores and reads data from a database and will need the right credentials to connect. Service A also connects to a message broker and places messages into it. Service C can pick messages from the message broker and, using some credentials, connect to a Bucket to store some calculations based on the messages it receives.

Common communication patterns in distributed applications.

No matter what logic these services are implementing, we can extract some constant behaviors and enable development teams to consume without the hassle of dealing with the low-level details or pushing them to make decisions around cross-cutting concerns that can be solved at the platform level.

To understand how this can work, we must look closely at what is happening inside these services. As you might know already, the devil is in the details. While from a high level perspective, we are used to dealing with services doing what is described in the previous figure, if we want to unlock an increased velocity in our software delivery pipelines, we need to go one level down to understand the intricate relationships between the components of our applications.

Let’s take a quick look at the challenges the application teams face when trying to change different services and infrastructure that our services require.

The challenges of coupling application and infrastructure

Fortunately, this is not a programming language competition, independent of your programming language of choice. If you want to connect to a database or message broker, you must add some dependencies to your application code. While this is a common practice in the software development industry, it is also one of the reasons why delivery speed is slower than it should be.

Coordination between different teams is the reason behind most blockers when releasing software. We have created architectures and adopted Kubernetes because we want to go faster. By using containers, we have adopted an easier and more standard way to run our applications. No matter in which language the application is written or which tech stack is used, if you give me a container with the application inside, I can run it. We have removed the application dependencies on the operating system and the software that we need to have installed in a machine (or virtual machine) to run your application, which is now encapsulated inside a container.

Unfortunately, we haven’t tackled the relationships and integration points between containers (our application’s services). We also haven’t solved how these containers will interact with application infrastructure components that can be local (self-hosted) or managed by a cloud provider.

Let’s take a closer look at where these applications heavily rely on other services and can block teams from making changes, pushing them for complicated coordination that can end up causing downtime to our users. We will start by splitting up the previous example into the specifics of each interaction.

Service-to-service interaction challenges

To send data from one service to another, you must know where the other service is running and which protocol it uses to receive information. Because we are dealing with distributed systems, we also need to ensure that the requests between services arrive at the other service and have mechanisms to deal with unexpected network problems or situations where the other services might fail. In other words, we need to build resilience in our services. We cannot always trust the network or other services to behave as expected.

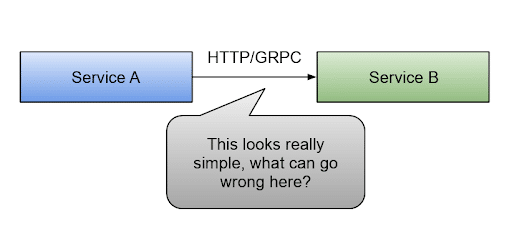

Let’s use Service A and Service B as examples to go deeper into the details. In the figure below, Service A needs to send a request to Service B.

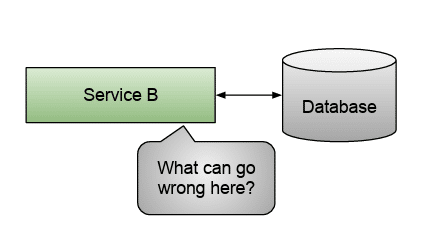

But let’s dig deeper into the mechanisms services can use internally. Suppose we leave the fact that Service A depends on the Service B contract (API) to be stable and not change for this to work on the side. What else can go wrong here?

As mentioned, development teams should add a resiliency layer inside their services to ensure that Service A requests reach Service B. One way to do this is to use a framework to retry the request if it fails automatically. Frameworks implementing this functionality are available for all programming languages.

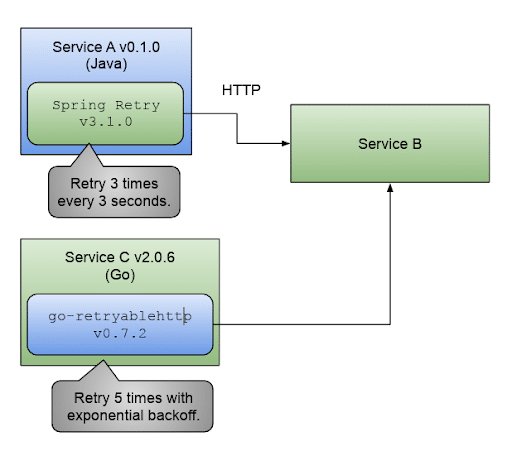

Tools like go-retryable or Spring Retry for Spring Boot add resiliency to your service-to-service interactions. Some of these mechanisms also include exponential backoff functionality to avoid overloading services and the network when things are going wrong.

Unfortunately, there is no standard library shared across tech stacks that can provide the same behavior and functionality for all your applications, so even if you configure both Spring Retry and go-retryablehttp with similar parameters, it is quite hard to guarantee that they will behave in the same way when services start failing.

The figure above shows Service A written in Java using the Spring Retry library to retry three times with a wait time of 3 seconds between each request when the request fails to be acknowledged by Service B. Service C, written in Go using the go-retryable http library, is configured to retry five times but using an exponential backoff (the retry period between requests is not fixed; this can provide time for the other service to recover and not be flooded with retries) mechanism when things go wrong.

Even if the applications are written in the same language and using the same frameworks, both services (A and B) must have compatible versions of their dependencies and configurations. If we push both Service A and Service B to have the versions of the frameworks, we are coupling them together, meaning we will need to coordinate the update of the other service whenever any of these internal dependency versions change. This can cause even more slowdowns and increase the complexity of coordination efforts.

On the other hand, using different frameworks (and versions) for each service will complicate troubleshooting these services for our operations teams. Wouldn’t it be great to have a way to add resiliency to our applications without modifying them?

Before answering this question, what else can go wrong?

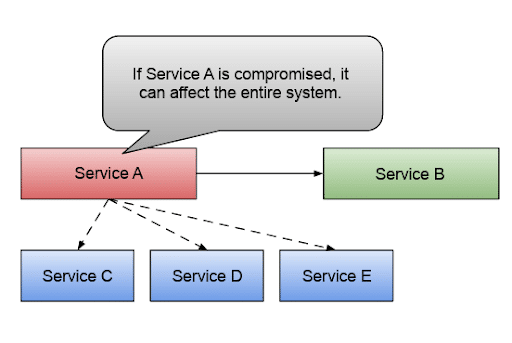

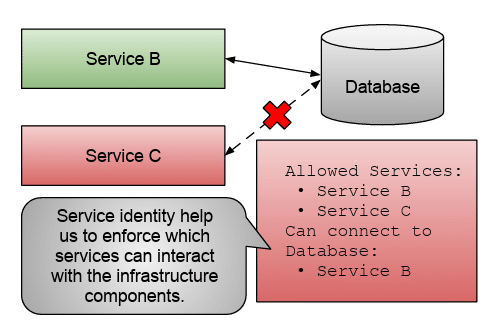

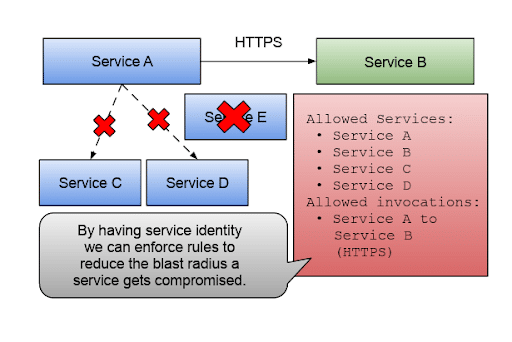

Something that developers often overlook relates to the security aspect of these communications. Service A and Service B don’t live in a vacuum, meaning other services surround them. If any of these services is compromised by a bad actor, having a free-for-all service-to-service invocation between all the services makes our entire system insecure. This is where having service identity and the right security mechanisms to ensure that, for this example, Service A can only call Service B is extremely important, as shown in the figure below.

Having a mechanism that allows us to define our service’s identity, we can define which service-to-service invocations are allowed and which protocols and ports are allowed for the communications to happen. The figure below shows how we can reduce the blast radius (how many services are affected if a security breach happens) by defining rules that enforce which services are allowed in our system and how they are supposed to interact.

How to reduce the blast radius by defining rules that enforce which services are allowed in our system and how they interact.

Having the right mechanisms to define and validate these rules cannot be easily built inside each service. Hence developers tend to assume that an external mechanism will be in charge of performing these checks.

As we will see in the following sections, service identity is something that we need across the board and not only for service-to-service interactions. Wouldn’t it be great to have a simple way to add service identity to our system without changing our application’s services?

Before answering this question, let’s look at other challenges teams face when architecting distributed applications. Let’s talk about storing and reading state, which most applications do.

Storing/reading state challenges

Our application needs to store or read state from persistent storage; quite a common requirement, right? You need data to do some calculations, then store the results somewhere so they don’t get lost if your application goes down. In our example, figure 3.6, Service B needed to connect to a database or persistent storage to read and write data.

What can go wrong here? Developers are used to connecting to different kinds of databases (relational, NoSQL, files, buckets) and interacting with them. But two main friction points slow teams from moving their services forward: dependencies and credentials.

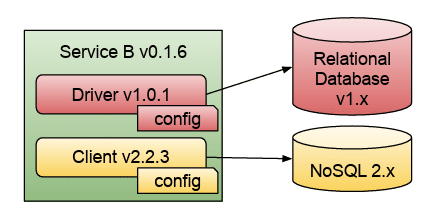

Let’s start by looking at dependencies. What kind of dependencies does Service B need to connect to a database? The diagram below shows Service B connecting to both a relational database and a NoSQL database. To achieve these connections, Service B needs to include a driver and a client library, plus the configuration needed to fine-tune how the application will connect to these two databases.

These configurations define the size of the connection pool (how many application threads can connect concurrently to the database), buffers, health checks, and other important details that can change how the application behaves.

Besides the configuration of the driver and the client, their versions need to be compatible with the version of the databases we are running, and this is where the challenges begin.

Once the application’s service is connected to the database using the client APIs, it should be fairly easy to interact with it. Whether by sending SQL queries or commands to fetch data or using a key-value API to read keys and values from the database instance, developers should know the basics to start reading and writing data.

Do you have more than one service interacting with the same database instance? Are they both using the same library and the same version? Are these services written using the same programming language and frameworks? Even if you manage to control all these dependencies, there is still a coupling that will slow you down. Whenever the operations teams decide to upgrade the database version, each service connecting to this instance might or might not need to upgrade its dependencies and configuration parameters. Would you upgrade the database first or the dependencies?

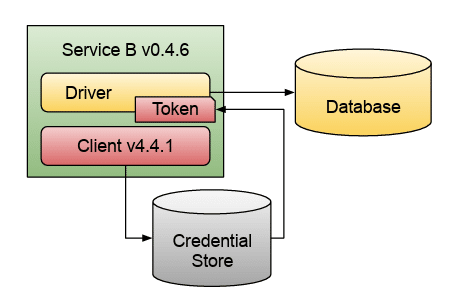

For credentials, we face a similar problem. It is quite common to consume credentials from a credential store like HashiCorp’s Vault. If not provided by the platform and not managed in Kubernetes, application services can include a dependency to consume credentials from their application’s code easily. The diagram below shows Service B connecting to a credential store, using a specific client library, to get a token to connect to a database.

Service B connecting to a credential store, using a specific client library, to get a token to connect to a database.

In chapters 1 and 2, we connected the Conference services to different components using Kubernetes Secrets. By using Kubernetes Secrets, we were removing the need for application developers to worry about where to get these credentials from.

Otherwise, if your service connects to other services or components that might require dependencies in this way, the service will need to be upgraded for any change in any of the components. This coupling between the service code and dependencies creates the need for complex coordination between application development teams, the platform team, and the operations teams in charge of keeping these components up and running.

Can we get rid of some of these dependencies? Can we push some of these concerns down to the platform team, so we remove the hassle of keeping them updated from developers? If we decouple these services with a clean interface, then the infrastructure and applications can be updated independently.

Before jumping into the next topic, I wanted to briefly talk about why having service identity at this level can also help reduce security problems when interacting with application infrastructure components. The figure above shows how similar service identity rules can be applied to validate who can interact with infrastructure components. Once again, the system will limit the blast radius if a service is compromised.

But what about asynchronous interactions? Let’s look at how these challenges relate to asynchronous messaging before jumping into the solutions space.

Asynchronous messaging challenges

With asynchronous messaging, you want to decouple the producer from the consumer. When using HTTP or GRPC, Service A needs to know about Service B, and both services need to be up to exchange information. When using asynchronous messaging, Service A doesn’t know anything about Service C. You can take it even further, where Service C might not even be running when Service A places a message into the message broker.

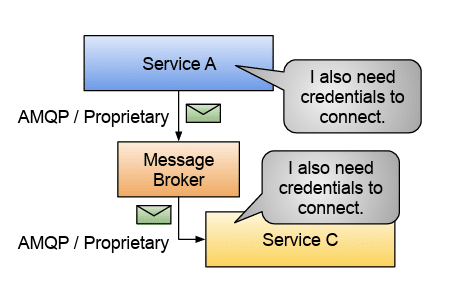

The figure below shows Service A placing a message into the message broker, which also needs credentials to connect. I also need credentials to connect the Service A Message Broker to Service C AMQP / Proprietary. The figure below shows Asynchronous messaging interactions at a later point in time. Service C can connect to the message broker and fetch messages from it.

Similar to HTTP/GRPC service-to-service interactions, when using a message broker, we need to know where the message broker is to send messages to or to subscribe to get messages from. Message brokers also provide isolation to enable applications to group messages together using the concept of topics. Services can be connected to the same message broker instance but send and consume messages from different topics.

When using message brokers, we face the same problems described with databases. We need to add a dependency to our applications depending on which message broker we decide to use, its version, and the programming language that we have chosen.

Message brokers will use different protocols to receive and send information. A standard increasingly adopted in this space is the CloudEvent specification from the CNCF. While CloudEvents is a great step forward, it doesn’t save your application developers from adding dependencies to connect and interact with your message brokers.

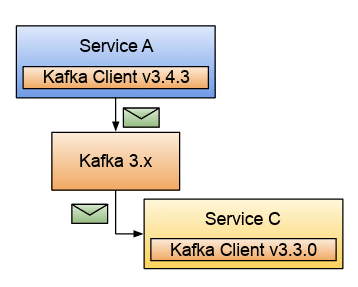

The figure above shows Service A, which includes the Kafka client library to connect to Kafka and send messages. Besides the URL, port, and credentials to connect to the Kafka instance, the Kafka client also receives configurations on how the client will behave when connecting to the broker, similar to databases. Service C uses the same client, but with different versions, to connect to the same broker.

Message brokers face the same problem as with databases and persistent storage. But unfortunately, with message brokers, developers will need to learn specific APIs that might not be that easy initially. Sending and consuming messages using different programming languages present more challenges and cognitive load on teams without experience with the specifics of the message broker at hand.

Same as with databases, if you have chosen Kafka, for example, it means that Kafka fits your application requirements. You might want to use advanced Kafka features that other message brokers don’t provide. However, let me repeat it here: we are interested in 95% of the cases where application services want to exchange messages to externalize the state and let other interested parties know. For those cases, we want to remove the cognitive load from our application teams and let them emit and consume messages without the hassle of learning all the specifics of the selected message broker.

By reducing the cognitive load required on developers to learn specific technologies, you can onboard less experienced developers and let experts take care of the details. Similar to databases, we can use service identity to control which services can connect, read, and write messages from a message broker. The same principles apply.

Dealing with edge cases (the remaining 5%)

There is always more than one good reason to add libraries to your application’s services. Sometimes these libraries will give you the ultimate control over how to connect to vendor-specific components and functionalities. Other times, we add libraries because it is the easiest way to get started or because we are instructed to do so. Someone in the organization decided to use PostgreSQL, and the fastest way to connect and use it is to add the PostgreSQL driver to our application code.

We usually don’t realize that we are coupling our application to that specific PostgreSQL version. For edge cases, or to be more specific, scenarios where you need to use some vendor-specific functionality, consider wrapping up that specific functionality as a separate unit from all the generic functionality you might consume from a database or message broker.

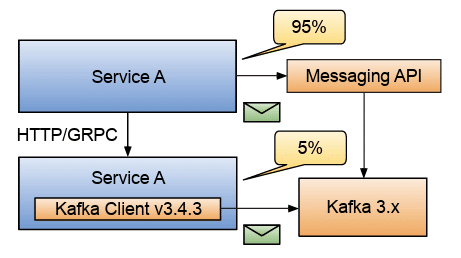

I’ve chosen to use async messaging as an example in the following figure, but the same applies to databases and credential stores.

Using some vendor-specific functionality and wrap it up as a separate unit from all the generic functionality you might consume from a database or message broker.

If we can decouple 95% of our services to use generic capabilities to do their work and encapsulate edge cases as separate units, we reduce the coupling and the cognitive load on new team members tasked to modify these services. Service A in the figure above is consuming a message API provided by the platform team to consume and emit messages asynchronously. We will look deeper into this approach in the next section [Check it out by downloading the entire book].

But more importantly, the edge cases, where we need to use some Kafka-specific features, for example, are extracted into a separate service that Service A can still interact with using HTTP or GRPC. Notice that the messaging API also uses Kafka to move information around. Still, for Service A, that is no longer relevant, because a simplified API is exposed as a platform capability.

When we need to change these services, 95% of the time, we don’t need team members to worry about Kafka. The messaging API removes that concern from our application development teams. For modifying Service Y, you will need Kafka experts, and the Service Y code will need to be upgraded if Kafka is upgraded because it directly depends on the Kafka client.

For this book, platform engineering teams should focus on trying to reduce the cognitive load on teams for the most common cases while at the same time allowing teams to choose the appropriate tool for edge cases and specific scenarios that don’t fit the common solutions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does coupling application code to infrastructure slow teams down?

To talk to databases, message brokers, or credential stores, services must typically add drivers, client libraries, and configuration into their own code. This creates tight coupling between:

- Service code and specific infrastructure versions

- Different services that share the same database, broker, or credentials

When infrastructure components (like database versions) change, each connected service may need dependency and configuration updates, forcing coordination between application, platform, and operations teams. This coordination becomes a major blocker to delivery speed and can increase the risk of downtime.

What problems arise in service-to-service communication?

For service-to-service calls, teams must handle:

- Knowing where another service is running and which protocol it uses

- Building resiliency into each service (retries, exponential backoff, etc.)

- Managing different retry frameworks and versions across languages and services

Because there is no standard resiliency library shared across all tech stacks, services often use different frameworks (for example, Spring Retry in Java and go-retryablehttp in Go) with different configurations and behaviors. This inconsistency makes troubleshooting harder and can require coordinated updates whenever a dependency changes, further slowing teams down.

What is service identity, and how does it help with security and infrastructure access?

Service identity refers to having a mechanism to:

- Define which services are allowed to call which other services, and over which protocols and ports

- Limit which services can connect to infrastructure components like databases or message brokers

By enforcing rules based on service identity, the system can reduce the “blast radius” if a service is compromised—only allowed interactions are possible, instead of a “free-for-all” between all services. These identity checks are difficult to build inside each service and are better handled by external mechanisms at the platform level.